Returning to exercise after a significant break can feel as if you’re starting from scratch. Your body remembers movement, but the strength, endurance, and coordination you once had seem to have vanished. This guide provides a research-grounded, structured workout plan to help you navigate your comeback safely and effectively, rebuilding your fitness without the setbacks of injury or burnout.

We’ll break down the science behind what happens when you stop training and explain how to leverage your body’s “muscle memory” to accelerate your return. You’ll get a detailed, phased plan that you can adapt to your needs, whether you’re at a gym or looking for a way to get back in shape at home. Let’s explore how to make your return to fitness a sustainable success.

Why Is It Harder to Work Out After a Break?

Working out is harder after a break because your body undergoes significant physiological changes, a process that is known as detraining, that reduces your fitness across cardiovascular, muscular, and metabolic systems (1).

These changes make previously manageable efforts feel much more strenuous.

Cardiovascular Declines

When you stop exercising, your cardiovascular system loses efficiency quickly. One of the first and most noticeable changes is a drop in your VO2max, which is the maximum amount of oxygen your body can use during intense exercise (2).

- Timeline of Decline: Research from 2021 published in the Journal of Sport Science showed that even two weeks of detraining can significantly reduce VO2max in trained runners (3). This decline is largely driven by a rapid decrease in blood plasma volume and stroke volume (the amount of blood your heart pumps with each beat) (2).

- Practical Impact: A lower VO2max means your heart and lungs must work harder to deliver oxygen to your muscles. This is why you feel out of breath much faster when you return to running or other cardio activities.

Muscular and Neural Regression

Your muscles also lose adaptations when you become inactive. This happens on both a neural and a structural level.

- Neural “Rust”: Your brain and nervous system become less efficient at recruiting muscle fibers (4). This loss of motor unit recruitment is why movements can feel clumsy or uncoordinated at first. It’s not just about muscle size – it’s about the brain-muscle connection weakening.

- Muscle Atrophy: Over a longer period, your muscle fibers, particularly the powerful Type II fast-twitch fibers, begin to shrink (5). This leads to a measurable loss of strength and power, making lifting weights or performing explosive movements more difficult. If aesthetics is a goal of yours, you’re going to look smaller as well.

Metabolic Shifts

Your body’s ability to manage energy also changes. Consistent exercise improves insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial density, both of which regress during a break.

- Reduced Insulin Sensitivity: Your muscles become less effective at taking up glucose from the blood for energy (2). This can contribute to feelings of fatigue and makes it harder to fuel your workouts.

- Decreased Mitochondrial Function: Mitochondria are the powerhouses of your cells, responsible for producing energy aerobically (6). Their number and efficiency decline with inactivity (7), meaning your body is less capable of producing sustained energy, increasing the perceived effort of any given task.

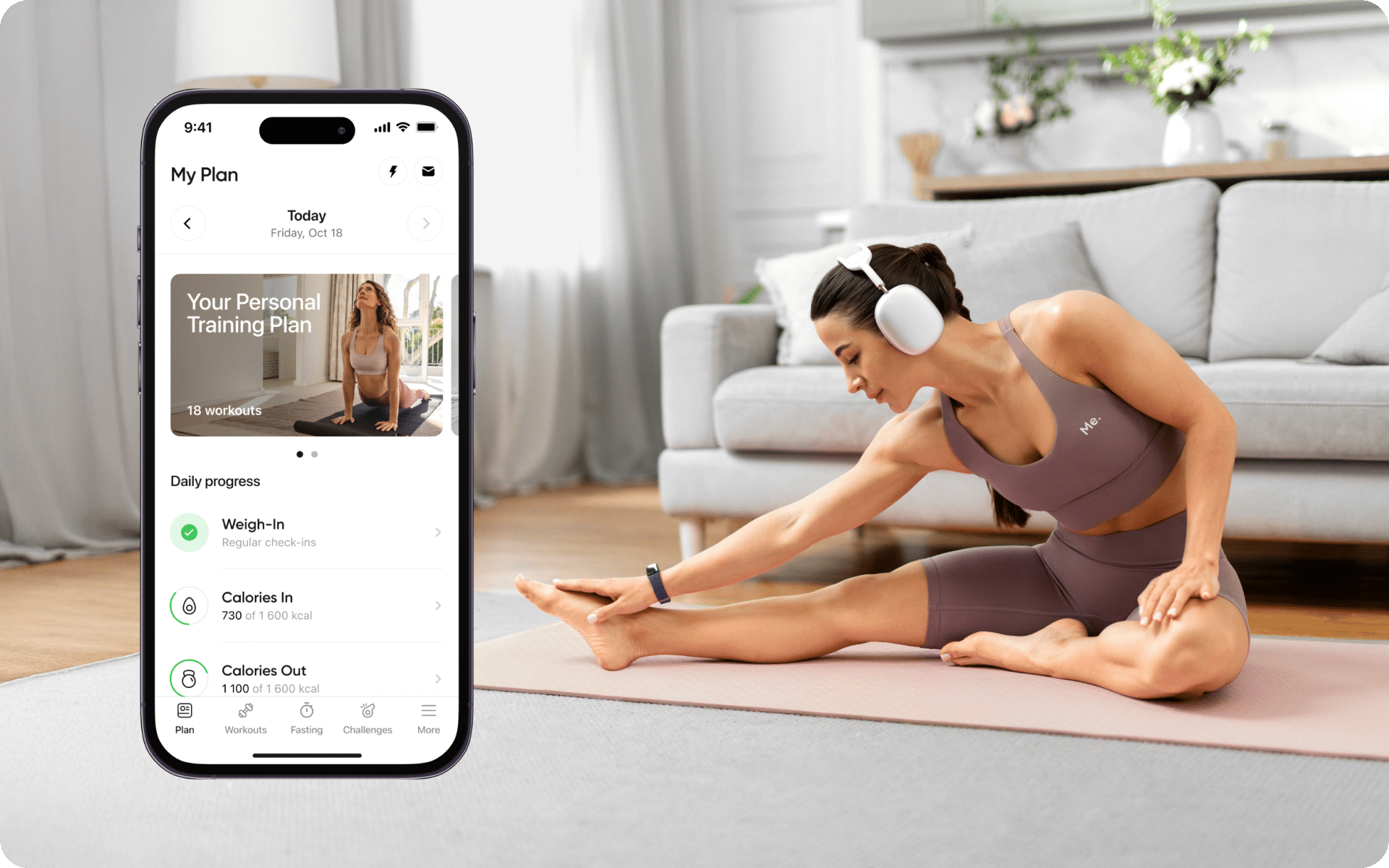

Reasons why BetterMe is a safe bet: a wide range of calorie-blasting workouts, finger-licking recipes, 24/7 support, challenges that’ll keep you on your best game, and that just scratches the surface! Start using our app and watch the magic happen.

Connective Tissue Deconditioning

A crucial and often overlooked aspect of detraining is what happens to your tendons, ligaments, and bones. These tissues adapt to load much more slowly than muscles (8).

- Reduced Load Tolerance: During a layoff, the stiffness and resilience of your connective tissues decrease (9). When you return to exercise, your muscles might feel ready for more work before your tendons and joints are.

- Injury Risk: This mismatch is a primary reason for overuse injuries like tendinopathies (e.g., Achilles or patellar tendonitis) and tendon ruptures when people ramp up their training volume or intensity too quickly after a break (10).

How to Start Exercising After Years of Not

To start exercising after years off, you must start with a foundational phase focused on re-establishing movement patterns and building cardiovascular endurance at a very low intensity. A gradual, structured approach is essential to allow your body – particularly your connective tissues – to adapt and to prevent injury.

Step 1: Medical Clearance and Baseline Assessment

Before you begin any new program, it’s wise to consult a healthcare professional, particularly if you have pre-existing health conditions, are over 45, or have been sedentary for many years (11). Once you’re cleared, you can establish a simple baseline.

- Resting Heart Rate: Measure your heart rate in the morning before getting out of bed. This gives you a baseline indicator of your cardiovascular fitness.

- Movement Screen: Perform basic movements like a bodyweight squat, a hinge (like picking up something light), a push-up against a wall, and a lunge. Note any stiffness, instability, or discomfort. This isn’t a test to pass or fail, but a way to gather information.

Step 2: Phase 1 – Re-acclimation (Weeks 1-2)

The goal of this initial phase is consistency and rebuilding your base, not intensity. Your focus should be on gentle, low-impact activity to prepare your body for more demanding work.

- Cardiovascular Exercise: Aim for 3 to 5 sessions per week of 20-30 minutes of low-intensity cardio. This should be done at a “conversational pace”, where you can easily hold a conversation. This corresponds to a Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) of 3-4 out of 10.

- Good Options: Brisk walking, cycling on a stationary bike, using an elliptical trainer, or swimming.

- Strength Training: Perform a full-body workout plan after a long break twice per week on non-consecutive days. Use very light loads or just your body weight.

- Focus: Master the movement pattern before adding weight. Concentrate on slow, controlled repetitions. A good tempo is 3 seconds for the lowering (eccentric) phase.

- Sample Workout: 2 sets of 10-15 repetitions of bodyweight squats, glute bridges, wall push-ups, and rows with a light resistance band.

Step 3: Listen to Your Body and Prioritize Recovery

Your body will give you signals. Pay attention to them.

- Soreness vs. Pain: Expect some mild muscle soreness (Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness or DOMS) 24-48 hours after a new workout. However, sharp, localized, or joint pain is a red flag. If you experience this, rest and reduce the intensity at your next session.

- Sleep and Nutrition: Prioritize 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night, as this is when your body repairs itself (12). Ensure you are eating enough protein (around 1.4 – 2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight) to support muscle repair (13).

Starting again after a long hiatus is a mental challenge as much as a physical one. Set realistic expectations and celebrate consistency over intensity.

If you are new to fitness and want to begin with the basics, you can find a helpful guide on a beginner workout at home without equipment.

Read more: Ultimate Pilates Mat Exercises List: Do Your Core A Real Favor

Can You Get Muscles Back After Years of Not Working Out?

Yes, you can absolutely get your muscles back after years of not working out, and you can often do it faster than it took to build them initially due to a phenomenon known as “muscle memory” (14).

The Science of Muscle Memory (Myonuclei)

The term “muscle memory” has a real biological basis in your muscle cells. Here’s how it works:

- Myonuclei Gain: When you train with weights, your muscle fibers are damaged. In response, satellite cells donate their nuclei to the muscle fibers to help repair and grow them. These new nuclei, called myonuclei, are permanent additions. Each nucleus can only manage a certain domain of the muscle cell, so adding more nuclei allows the cell to grow larger (hypertrophy) (15).

- Myonuclei Retention: When you stop training and your muscles shrink (atrophy), you lose muscle protein and volume, but a 2019 review confirmed that these myonuclei stick around. They remain dormant within the smaller muscle fibers (16).

- Faster Regrowth: When you resume training, these retained myonuclei are quickly reactivated. As the “command centers” for protein synthesis are already in place, your muscle fibers can rebuild and grow at an accelerated rate compared to someone who is training for the first time.

Recent 2025 research from the University of Illinois has even suggested that retraining can lead to additional muscle gains beyond what was previously achieved, thanks to this robust cellular machinery (17).

How Strength Returns

The process of regaining strength follows a predictable pattern, starting with neural adaptations and followed by physical growth.

- Neural Adaptations (Weeks 1-4): The first gains you experience are primarily neural. Your brain and nervous system relearn how to efficiently recruit motor units and coordinate muscle contractions (18, 19). This is the “rusty” feeling going away, and your strength will increase rapidly during this phase, even before significant muscle growth is visible.

- Hypertrophy (Weeks 4-12+): After the initial neural improvements, continued gains come from the actual growth of muscle fibers (hypertrophy) (18). With consistent progressive overload (gradually increasing the demand on your muscles), the retained myonuclei drive a rapid increase in protein synthesis, leading to faster muscle regrowth (20).

Realistic Expectations for Regaining Muscle

While regrowth is faster, it’s not instant. The speed will depend on several factors:

- Length of the Break: A 6-month break will be quicker to recover from than a 10-year break.

- Previous Fitness Level: The more muscle and strength you had before, the more potential you have to regain.

- Age and Hormones: Younger individuals and those with more favorable hormonal profiles (e.g. higher testosterone) may regain muscle more quickly.

- Training, Nutrition, and Sleep: Your results are directly tied to the quality of your program, your protein intake, and your recovery.

For anyone who has previously laid a solid foundation of muscle, the potential to regain it is high. The cellular architecture for growth remains, waiting to be reactivated.

Read more: Easy Calisthenics Moves That Actually Work: A No-Nonsense Beginner’s Guide

What Happens when You Start Exercising After a Long Time?

When you start exercising after a long time, your body initiates a cascade of positive adaptations across your cardiovascular, muscular, and neurological systems (18, 21), but it also experiences temporary stress and soreness as it adjusts to the new demands.

Immediate and Short-Term Effects (First 1-4 Weeks)

In the first few weeks, the changes are dramatic but can also be uncomfortable.

- Increased Heart Rate and Perceived Exertion

Your first few workouts will feel hard. Your heart rate will spike quickly, and your breathing will be labored because your cardiovascular system has lost its efficiency. An activity that was once a 5/10 on the effort scale might now feel like an 8/10.

- Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)

You’ll likely experience significant muscle soreness 24 to 48 hours after your workouts. This is believed to be caused by microscopic tears in your muscle fibers, a normal part of the adaptation process, particularly after eccentric (lengthening) movements such as lowering a weight or running downhill (22).

- Rapid Neural Improvements

You will notice improvements in coordination and strength very quickly. Lifts that felt awkward in week one will feel smoother and stronger by week three. This is your nervous system optimizing its firing patterns, not yet significant muscle growth.

- Blood Volume Expansion

One of the fastest adaptations is an increase in your blood plasma volume. Within 1-2 weeks of consistent aerobic exercise, your body increases its fluid volume to make blood circulation more efficient, which lowers your heart rate for a given effort (23).

Medium-Term Adaptations (Weeks 4-12)

After the initial shock, your body begins to make more durable structural changes.

- Cardiovascular Improvements

Your VO2max will start to increase meaningfully. Your heart becomes stronger, pumping more blood with each beat (increased stroke volume), and your muscles get better at extracting oxygen from the blood. You’ll be able to work out for longer and at higher intensities without feeling as fatigued.

- Muscle Growth (Hypertrophy)

This is when visible changes in muscle size begin to occur, assuming you’re following a progressive strength training program and consuming adequate protein. Your body is now moving past neural adaptations and is actively building larger, stronger muscle fibers.

- Improved Metabolic Health

Your body’s insulin sensitivity improves, which means you become better at using carbohydrates for fuel and storing them in your muscles as glycogen. Your mitochondrial density increases, enhancing your body’s ability to produce energy from fat and carbohydrates.

- Connective Tissue Strengthening

Your tendons, ligaments, and bones start to get stronger. This is a slow process, but consistent, progressive loading signals them to become denser and more resilient, which is essential for long-term injury prevention.

Long-Term Benefits (3+ Months)

Sticking with your routine yields profound health and performance benefits.

- Sustainable Fitness

Exercise becomes a habit. Workouts feel less like a chore and more like a part of your routine. You have built a solid fitness base that allows you to pursue more specific goals, such as running a 5K or lifting a certain weight.

- Reduced Disease Risk

Consistent exercise significantly lowers your risk of chronic diseases, including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer (24).

- Improved Mental Health

You’ll likely experience improved mood, reduced anxiety, and better cognitive function. Exercise is a powerful tool for stress management and enhancing brain health (25, 26).

Starting to exercise again is a process of re-adapting. It requires patience through the initial discomfort, but the rewards are a stronger, healthier, and more resilient body. This journey of transformation is something you can start at any stage. For more guidance on restarting your fitness journey, read about how to start exercising again.

What Is the Best Exercise After a Long Period of Inactivity?

The best exercise after a long period of inactivity is a combination of low-impact cardiovascular activity and foundational strength training This dual approach safely rebuilds your endurance and functional strength simultaneously.

There is no single “best” exercise, but rather a best type of program that balances these two critical components.

Component 1: Low-Impact Cardiovascular Exercise

Starting with low-impact cardio minimizes the stress on your deconditioned joints, bones, and tendons, which are highly susceptible to injury early on. It elevates your heart rate to improve cardiovascular health without the jarring impact of activities such as running (27). This allows your connective tissues to adapt gradually.

Some low-impact cardio options include:

- Brisk Walking: The most accessible option. Start with 20-30 minutes, 3-4 times a week, focusing on maintaining a pace where you can still talk.

- Cycling (Stationary or Outdoor): Excellent for building leg strength and endurance with zero impact. It’s a great choice if you have knee or hip sensitivities.

- Elliptical Trainer: Mimics running motion without the impact, engaging both your upper and lower body.

- Swimming or Water Aerobics: The buoyancy of water supports your body weight, making it an ideal environment for gentle, full-body conditioning.

Component 2: Foundational Strength Training

Strength training is essential for rebuilding lost muscle, improving metabolic health, and increasing bone density (28). The focus should be on mastering basic human movement patterns with light weight or body weight. A full-body workout plan after a long break is an efficient approach.

Full-body workouts hit all major muscle groups 2-3 times per week, which maximizes the frequency of the muscle-building stimulus without requiring you to be in the gym every day (29). This is ideal for beginners and those returning to exercise.

Key movement patterns to include:

- Squats: (e.g. bodyweight squats, goblet squats) – Build lower-body strength.

- Hinges: (e.g. glute bridges, Romanian deadlifts with light weight) – Strengthen the glutes and hamstrings, crucial for protecting the lower back.

- Pushes: (e.g., wall push-ups, incline push-ups, dumbbell bench press) – Develop upper-body pushing strength.

- Pulls: (e.g. band rows, dumbbell rows) – Balance pushing movements by strengthening the back.

- Carries: (e.g. farmer’s walks with light dumbbells) – Build core stability and grip strength.

This combined approach is supported by modern research.

A 2025 study in Frontiers in Aging involving middle-aged adults found that a program combining aerobic and resistance training was highly effective for restoring fitness markers and metabolic health in sedentary adults (30). It creates a well-rounded foundation for a healthy and capable body.

BetterMe: Health Coaching app helps you achieve your body goals with ease and efficiency by helping to choose proper meal plans and effective workouts. Start using our app and you will see good results in a short time.

What Is a Gentle Workout Plan After a Long Break?

A gentle workout plan after a long break is structured in phases, starting with extremely low intensity and volume and progressing slowly over 8-12 weeks. This allows your body’s systems, especially slow-adapting connective tissues, to safely reacclimate to exercise.

The Phased Approach to a Gentle Return

This plan is designed to be a template. You must listen to your body and adjust the routine based on how you feel. The RPE (rate of perceived exertion) scale of 1-10 is your guide, where 1 is sitting on the couch and 10 is an all-out maximal effort.

Phase 1: Foundation and Re-acclimation (Weeks 1-3)

Goal: Build consistency and reintroduce movement without causing excessive stress.

Focus: Low impact, low intensity, high frequency.

- Cardio: 4-5 times per week.

- Duration: Start at 20 minutes and gradually increase to 30 minutes.

- Intensity: RPE 3-4/10 (light pace, can easily hold a conversation).

- Examples: Walking, stationary bike, elliptical.

- Strength: 2 times per week (non-consecutive days). This is a full-body workout plan for after a long break.

- Volume: 2 sets of 10-15 reps per exercise.

- Intensity: RPE 5/10 (light weight, focus on form).

- Sample Week 1 Workout:

- Bodyweight squats

- Glute bridges

- Wall push-ups

- Seated band rows

- Plank (hold for 20-30 seconds)

Phase 2: Progressive Overload (Weeks 4-8)

Goal: Gradually increase the demand on your body to stimulate adaptation.

Focus: Introduce slight increases in duration, volume, or load.

- Cardio: 4-5 times per week.

- Duration: Build from 30 to 45 minutes.

- Intensity: Mostly RPE 4-5/10, but introduce one session with short intervals (e.g. 5 rounds of 1 minute at RPE 6-7, followed by 2 minutes of easy recovery).

- Strength: 2-3 times per week.

- Volume: Progress to 3 sets of 8-12 reps.

- Intensity: RPE 6-7/10 (challenging, but you could do a few more reps if needed). Start adding light weight (e.g. goblet squats with a light dumbbell).

- Sample Week 5 Workout:

- Goblet squats

- Dumbbell Romanian deadlifts

- Incline push-ups or dumbbell bench press

- Dumbbell rows

- Farmer’s walks

This is an ideal structure for almost everyone, as it’s so effective and the principles of progressive overload are universal. For a get-back-in-shape workout plan at home, all exercises can be done with body weight or a simple set of resistance bands and dumbbells.

For busy parents, finding time can be the biggest hurdle. You can explore a variety of at-home workouts for moms.

Phase 3: Specificity and Intensity (Weeks 9-12+)

Goal: Start tailoring your training toward your specific fitness goals.

Focus: Increase intensity and add more complex or specific movements.

- Cardio: 3-5 times per week.

- Structure: You can now have more structured sessions, such as one long, easy session (60+ minutes at RPE 4), one threshold session (e.g. 20 minutes at RPE 7-8), and 1-2 easy recovery sessions.

- Strength: 2-3 times per week.

- Volume: Vary the rep ranges. You could have some exercises in the 5-8 rep range (for strength) and others in the 10-15 range (for hypertrophy and endurance).

- Intensity: RPE 7-8/10 on your main lifts.

- Progression: Continue to add weight or reps weekly. Consider introducing more advanced exercises if your form is solid.

Important Rule: Never increase the total weekly volume (duration x intensity) by more than 10% per week. This rule of gradual progression is your best defense against injury (31).

How Long Does It Take to Get Back in Shape After Years Off?

It typically takes between 3 and 6 months to get back to a good level of fitness after years off, but regaining your previous peak fitness level could take anywhere from 6 to 12 months or more, depending on your prior condition and the length of your break.

The Timeline of Adaptation

Your body adapts at different rates. Here’s a realistic breakdown of what to expect.

- First Month (Weeks 1-4): The Re-adaptation Phase

- What you’ll feel: This phase is often the hardest. You’ll feel out of shape, sore, and possibly discouraged.

- What’s happening: Your body is making rapid neural adaptations and increasing blood plasma volume. You’ll see big improvements in coordination and may notice your resting heart rate start to drop, but you won’t see much visible change.

- Months 2-3 (Weeks 5-12): The Improvement Phase

- What you’ll feel: Workouts start to feel more manageable. You can push a little harder and for longer. Muscle soreness becomes less intense.

- What’s happening: This is where cardiovascular fitness (VO2max) and muscular endurance show significant improvement. Muscle growth (hypertrophy) begins in earnest. Your body composition may start to change, with a potential decrease in fat and an increase in muscle mass.

- Months 4-6 (Weeks 13-24): The Consolidation Phase

- What you’ll feel: You now feel “fit”. You’ve established a routine, and exercise is likely a consistent part of your life. You can tackle more challenging workouts and set specific performance goals.

- What’s happening: Your connective tissues have become more robust, lowering your injury risk. You have built a solid foundation of both strength and endurance. A specific workout plan after a long break for females or a workout plan after a long break for males can now be more specialized towards individual goals, such as advanced strength or endurance sports.

- Months 6+: The Optimization Phase

- What you’ll feel: You’re close to or have surpassed your previous fitness levels. Progress is slower now and requires more strategic planning (periodization, deloads).

- What’s happening: You’re now fine-tuning your fitness, working on specific strengths or weaknesses.

Factors That Influence Your Timeline

- Muscle Memory: As previously mentioned, if you were very fit before, you’ll regain fitness faster than a true beginner.

- Consistency: This is the single most important factor. Someone who trains consistently 3 times a week will progress much faster than someone who trains sporadically 5 times one week and zero the next.

- Age: While you can build fitness at any age, younger individuals may adapt slightly faster due to hormonal advantages.

- Lifestyle Factors: Your progress will be accelerated by quality sleep, a supportive diet rich in protein, and effective stress management. A get-back-in-shape workout plan at home can be just as effective as a gym plan if it is followed consistently.

Ultimately, “in shape” is a subjective term. The goal isn’t to race back to where you were, but to build a sustainable habit that makes you feel strong, healthy, and capable for the long term.

No, 2 weeks off won’t ruin your gains, but it will cause a noticeable decline in performance. Research has shown measurable drops in cardiovascular fitness (VO2max) and a slight decrease in maximal strength, primarily due to neural and blood volume reductions (3). However, muscle size (hypertrophy) is largely unaffected in such a short period, and you can expect to return to your previous performance levels within 1-2 weeks of consistent training. It’s never too late in life to start exercising. Studies have consistently shown that individuals in their 60s, 70s, and beyond can make significant gains in muscle mass, strength, bone density, and cardiovascular health with a properly structured training program (32). The benefits of exercise for improving quality of life and reducing age-related decline are profound at any age (33). You don’t “lose” muscle memory to begin with, so you don’t need to regain it. The biological basis of muscle memory – the myonuclei acquired during previous training – is retained in your muscle cells even during long periods of inactivity (34). When you start training again, these nuclei are reactivated, which allows for much faster muscle and strength regain compared to when you first started (34). Yes, you can absolutely reverse many of the negative health effects of a sedentary lifestyle. Starting a consistent exercise program can improve cardiovascular health, increase insulin sensitivity, build muscle mass, strengthen bones, and reduce the risk of numerous chronic diseases (35, 36). While some long-term structural changes may not be fully reversible, a move from a sedentary to an active lifestyle is one of the most powerful changes you can make for your long-term health and well-being.Frequently Asked Questions

Will 2 weeks off ruin gains?

Is it too late in life to start exercising?

Can you regain lost muscle memory?

Can you reverse years of a sedentary lifestyle?

The Bottom Line

Returning to exercise after a long break is a journey of rediscovery. By respecting your body’s current condition and following a structured, patient approach, you can rebuild your fitness on a stronger foundation than before.

The key is to start slow, progress gradually, and listen to the feedback your body provides. This methodical process will not only get you back in shape but will also equip you with the knowledge to maintain your health and performance for years to come.

DISCLAIMER:

This article is intended for general informational purposes only and does not serve to address individual circumstances. It is not a substitute for professional advice or help and should not be relied on for making any kind of decision-making. Any action taken as a direct or indirect result of the information in this article is entirely at your own risk and is your sole responsibility.

BetterMe, its content staff, and its medical advisors accept no responsibility for inaccuracies, errors, misstatements, inconsistencies, or omissions and specifically disclaim any liability, loss or risk, personal, professional or otherwise, which may be incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and/or application of any content.

You should always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or your specific situation. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of BetterMe content. If you suspect or think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor.

SOURCES:

- Detraining: Loss of Training-Induced Physiological and Performance Adaptations. Part I (2000, link.springer.com)

- Cardiorespiratory and metabolic characteristics of detraining in humans (2001, journals.lww.com)

- Two weeks of detraining reduces cardiopulmonary function and muscular fitness in endurance athletes (2021, onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- Neuromuscular adaptations to detraining following resistance training in previously untrained subjects (2005, link.springer.com)

- Cardiorespiratory and metabolic consequences of detraining in endurance athletes (2024, frontiersin.org)

- Mitochondria: It is all about energy (2023, frontiersin.org)

- Mitochondrial dysfunction induces muscle atrophy during prolonged inactivity: A review of the causes and effects (2018, researchgate.net)

- Functional Adaptation of Connective Tissue by Training (2019, germanjournalsportsmedicine.com)

- Time Course of Changes in Muscle and Tendon Properties During Strength Training and Detraining (2010, journals.lww.com)

- The Role of Detraining in Tendon Mechanobiology (2016, frontiersin.org)

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition (2018, odphp.health.gov)

- Sleep and muscle recovery: endocrinological and molecular basis for a new and promising hypothesis (2011, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise (2017, jissn.biomedcentral.com)

- Skeletal muscle memory (2023, journals.physiology.org)

- Going nuclear: Molecular adaptations to exercise mediated by myonuclei (2022, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Skeletal Muscles Do Not Undergo Apoptosis During Either Atrophy or Programmed Cell Death-Revisiting the Myonuclear Domain Hypothesis (2019, frontiersin.org)

- Muscle memory of exercise optimizes mitochondrial metabolism to support skeletal muscle growth (2025, journals.physiology.org)

- Adaptations to Endurance and Strength Training (2018, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- The knowns and unknowns of neural adaptations to resistance training (2020, link.springer.com)

- Myonuclei acquired by overload exercise precede hypertrophy and are not lost on detraining (2010, pnas.org)

- Exercise Physiology (2024, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Mechanisms and Treatment of Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness in Athletes – A Review (2022, researchgate.net) 22

- Normal Versus Chronic Adaptations to Aerobic Exercise (2023, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Exercise sustains the hallmarks of health (2023, sciencedirect.com)

- Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review (2023, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Physical Activity and Brain Health (2019, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- The (Many) Benefits of a Cardio Workout (2023, health.clevelandclinic.org)

- Strength training: Get stronger, leaner, healthier (2023, mayoclinic.org)

- Progression Models in Resistance Training for Healthy Adults (2009, journals.lww.com)

- Effects of combined aerobic-resistance training on health-related quality of life and stress in sedentary adults (2025, frontiersin.org)

- Progressive Overload Explained: Grow Muscle & Strength Today (n.d., blog.nasm.org)

- Muscle Mass and Strength Gains Following Resistance Exercise Training in Older Adults 65–75 Years and Older Adults Above 85 Years (2023, journals.humankinetics.com)

- Exercise Attenuates the Major Hallmarks of Aging (2015, journals.sagepub.com)

- Myonuclear permanence in skeletal muscle memory: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of human and animal studies (2022, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Too Little Exercise and Too Much Sitting: Inactivity Physiology and the Need for New Recommendations on Sedentary Behavior (2008, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review (2019, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)